Introduction

A university degree can have great benefits.

- It can equip people with the high-level technical expertise required to do certain jobs, like Engineering and Medicine;

- a degree from a top university can open many doors later in life due to the valuable credentials one earns;

- one can mix with other talented, driven people and make invaluable life connections;

- higher education is also a useful transitional period for an individual to gain independence living away from home yet still within the security of a broader structure of an institution.

In our culture today, we are so used to taking for granted that going to university is a good and aspirational thing to aim for, we rarely take time to consider why this belief is so ingrained (it hasn’t always been) and to consider the other side of the argument i.e. the potential costs of university higher education and why one may consider alternative routes after leaving school. (YouGov: nearly half of UK public say university participation is too high).

We will explore some topics relating to this below.

50% of young people into higher education.

In September 1999, Tony Blair announced his target to get 50% of young adults to enter higher education by 2010. (Plan for huge rise in university numbers | UK news | The Guardian)

At the time it was 39%, so this marked an 11% increase (SN02630.pdf)

The rationale given for this was that university graduates had “higher-level skills” and so were more employable / had more opportunities and, therefore, by increasing the number of graduates, we, as a country, could participate more meaningfully in the “knowledge economy”.

This 50% threshold was achieved late last decade, however with hindsight, has it made life better for young people?

Why do companies prefer to hire university graduates?

Firstly, barring specialised vocational degrees, one has to think why employers were preferentially hiring people with degrees in the first place? In many cases, it wasn’t due to what was learned on the course, it was because the barrier to entry to get into the courses acted as a filter selecting the brightest and most industrious people. Employing these people is desirable as, probabilistically, they will produce the most value for the company (a company wants to maximise its value per employee). (Signalling (economics) – Wikipedia)

So, if you expand the number of people who have a degree, it doesn’t mean more people are suddenly bright and talented (as these are relative terms), instead, it dilutes the significance of having a degree as being an indicator of work-ethic and competence.

Sought-after courses at top universities get more competitive as the number of applicants increase and they can’t increase their intake much (if at all). (Has Oxbridge Become More Competitive? 10 Year Review) So, the way to increase participation is to lower entry requirements which is done by increasing the number of universities and courses available. (List of universities in England – Wikipedia)

The culture is in an oxymoronic state of the unquestioned dogma of “we must get more people into university than last year” and the real-world value to the students these courses are bestowing.

Universities and political ideology

Following from this point, nowadays there is worry that university campuses have become “ideological indoctrination chambers”, conditioning students toward radical politics, ideological fragility and conformity, the prioritisation of emotion-based thinking over critical thought and a glorification of victimhood. This hostile, censorious puritanism has grown to a point where it is difficult to reverse course.

(40% of Millennials OK with limiting speech offensive to minorities | Pew Research Center,

“Freedom-restricting harassment” of gender critical academics creating barriers to research, government review finds – The Free Speech Union,

A culture of victimhood and intolerance – spiked,

The New Puritans: How the Religion of Social Justice Captured the Western World: Amazon.co.uk: Doyle, Andrew: 9780349135328: Books,

The New Clerisy: How Thomas Sowell Predicted the Rise and Ruin of DEI Bureaucracies | Hoover Institution The New Clerisy: How Thomas Sowell Predicted the Rise and Ruin of DEI Bureaucracies)

This isn’t just a phenomenon within university student cohorts, but also amongst teaching staff. In the UK, the Times Higher Education (THE) surveys of university staff (including academics and professional/support roles) revealed a stark imbalance:

In the US, FIRE 2024 Faculty Survey (largest recent survey: 6,269 faculty at 55 major US colleges/universities):

- ~61% identify with or lean Democrat.

- ~12% identify with or lean Republican.

(Silence in the Classroom: The 2024 FIRE Faculty Survey Report | The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression)

Yale University Analyses (Buckley Institute):

- 2024: ~77% Democrat-affiliated, <3% Republican (overall ratio ~28:1).

- 2025: 82.3% Democrat, 2.3% Republican (ratio >36:1); 27 departments with zero Republicans.

(NEW: Faculty Political Diversity at Yale: Democrats Outnumber Republicans 28 to 1 – Buckley Institute)

This means that the “Overton Window” drifts and it is very difficult for individuals with their heads screwed on not to be taken along, to some degree, by this ideological undercurrent. (Overton window | Political Science, Origin, Examples, Shifts, & Criticism | Britannica)

Do modern jobs make us tick?

It is also worth considering our history. One important aspect of human nature is the desire to feel useful, needed and valued. For most of human history, our jobs aligned with this as we lived in small communities where each person could easily see the impact of the work they were doing as they were providing a good or service directly to that small community. (Dunbar’s number – Wikipedia)

For example there would usually be someone who was “the butcher” and he/she would provide meat to the community, another would be the seamstress, carpenter, run the pub etc. etc. One issue that many white-collar jobs have nowadays is a dystopian disconnect between the work one is doing and the value / use it is contributing to the community. (Organization Size and How it Impacts Employee Happiness | Friday Pulse, Let’s call time on the bulls–t jobs plaguing Britain’s offices, A Brief History of the Corporate Form and Why it Matters – Fordham Journal of Corporate and Financial Law)

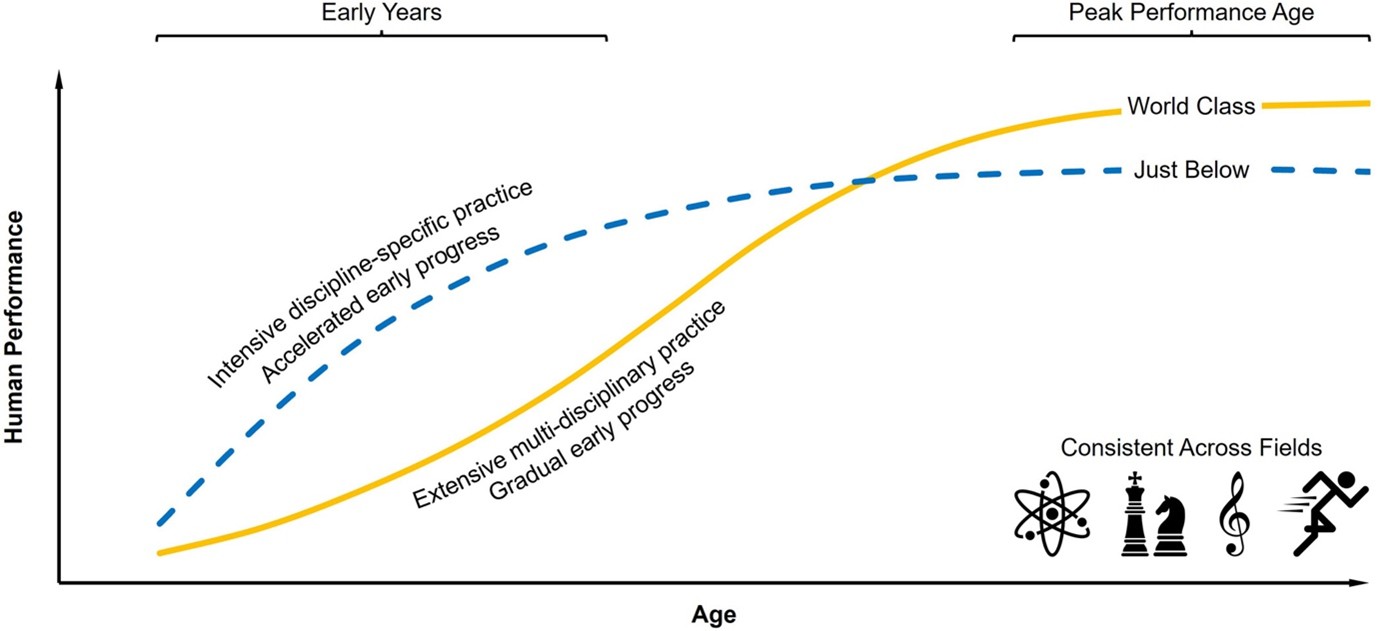

While many may aspire to be senior management of companies, the brutal reality is that the number of these positions hasn’t increased at the rate the supply of graduates has increased, meaning many people will be on a trajectory for middle management of large corporate leviathans. A lifetime as a good (yet easily replaceable) cog. One could make the argument that trade jobs align more closely with the value and fulfilment incentives to which our brains are programmed to be most receptive; a carpenter, electrician or builder can look back on a decade of work and see all the houses they have built, now inhabited by happy families.

Debt and apprenticeships

Debt; the average student in England graduates with £53,000 worth of debt, which they will spend decades paying back. (Student loan statistics – House of Commons Library)

This is a cost and one needs to consider whether the benefits of the degree they’ll receive outweigh this cost. If you want to be a neurosurgeon then it certainly will do, however so many corporate firms today run apprenticeship schemes for people straight out of school; it does beg the question that if you are aiming for this career, will a degree in English and Film Studies from Exeter be useful in achieving this end, and will it be worth taking on that debt for? Who’s to say the apprenticeship candidate 4 years down the line could be the uni graduate’s boss when he/she joins! (Best apprentices earn £50,000 more than many graduates – The Sutton Trust)

Conclusion

The take-home message of this isn’t to dissuade people from going to university, but more to try and give the side of the argument less commonly given to enable people to make a better decision. To quote Thomas Sowell: “There are no solutions, only trade-offs,” so if you are considering university, make sure you pick the pathway where the benefits and trade-offs are best for you in your current situation and for your aspirations.

The unprecedented surge in the coronavirus brought the world to a standstill. However, the situation is now easing with the development and deployment of vaccines against the pandemic –

The unprecedented surge in the coronavirus brought the world to a standstill. However, the situation is now easing with the development and deployment of vaccines against the pandemic –